In addition, we demonstrate more

abstract uses of motion blur. In this sequence (originally visualized in

), instead of forming motion tails,

alternating frames are blurred. This was inspired by examples of the

diagrammatic elements used in traditional comics (

), and while it clearly has less of a basis in reality than

"motion tails," viewers still found the effect interesting and

informative.

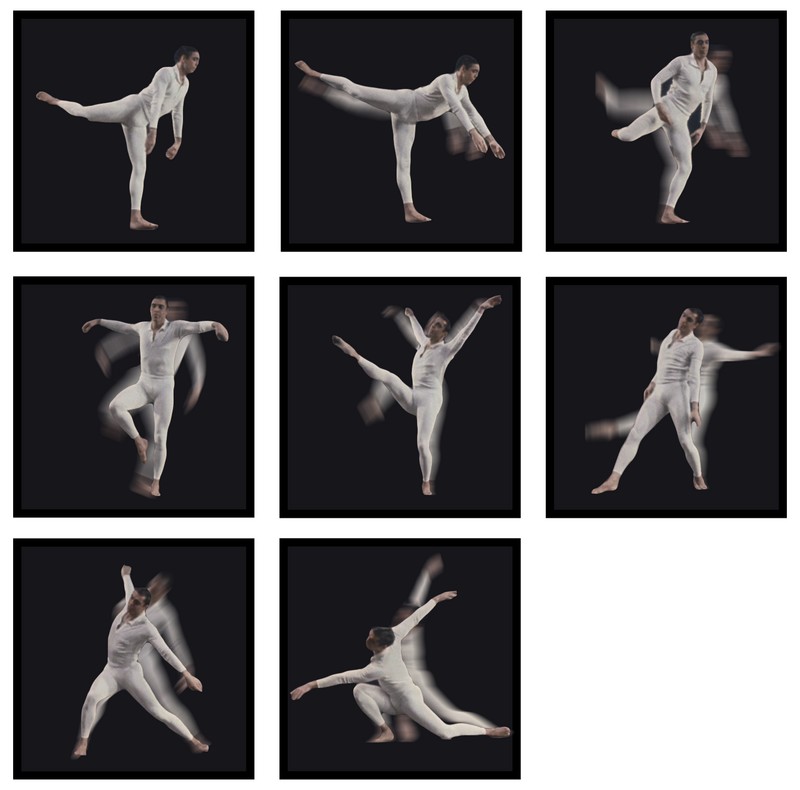

This same technique can be applied to the comic visualizations presented in

the last section.

Figure 21 shows an example of

this, using the same dance sequence as before. This is much harder

than the skating example, since different parts of the body move in

completely different directions, and hence must be blurred separately.

Figure 21

Figure 21: Motion blur lines.

Video

Motion Lines

While motion blur is an intuitive way to describe movement, it has its

drawbacks: it takes up quite a bit of screen real estate and loses

much of the information present in the original image. Our "motion

tails" approach, mixing motion blur with static strobe images, helps

with these issues, but doesn't solve them entirely. An alternate

approach is to study the language of motion developed by comic book

artists (

Figure 5), who have been

struggling with many of these issues for decades.

The most common diagramatic element found in comics is the "motion

line," a line that traces a point in space throughout the duration of

the action. In many cases, this is a simplified form of motion blur,

with lines streaking behind the moving object. At the same time,

motion lines have many degrees of freedom that can be mapped to qualities of the motion: length,

width, frequency, color, opacity, etc. In the following examples, we

explore a small subset of this space to demonstrate the power of these

techniques, which would all be impossible to create with traditional

photography.

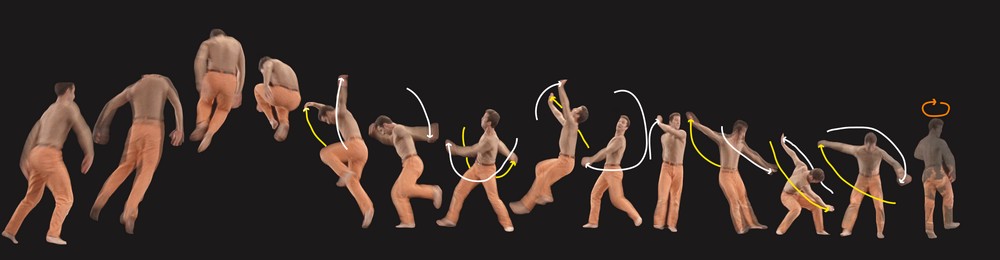

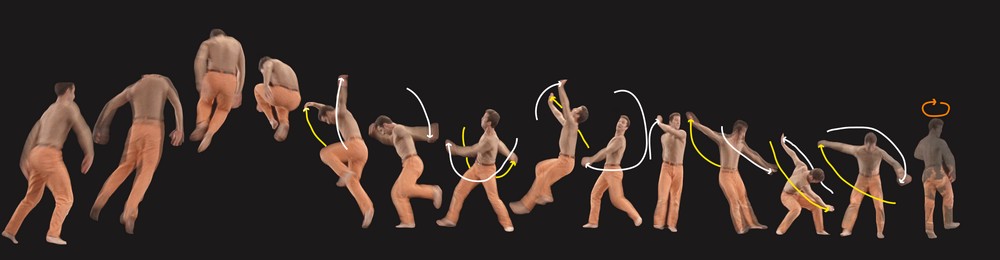

In our first example (

Figure 22), we add

diagrammatic arrows to the visualization depicted in

Figure 15. These arrows were

added using Adobe Illustrator. We felt this example could

especially benefit from motion lines, since the paths of the dancer's movements were

not always clear. The motion lines help clear up this

ambiguity. The lines start at the last position of the arms in the previous

sprite, and sweep to their new position. Different colors were

used for the two arms. Finally, a third color was used to

indicate whole body rotation at the end.

Figure 22

Figure 22: Arrow motion lines.

Video

Though these lines do add useful

information, we found it difficult to create aesthetically pleasing

results using Illustrator. To help us create the rest of the

examples in the section, we developed a small interactive tool for

drawing smooth motion lines and compositing them into the scene.

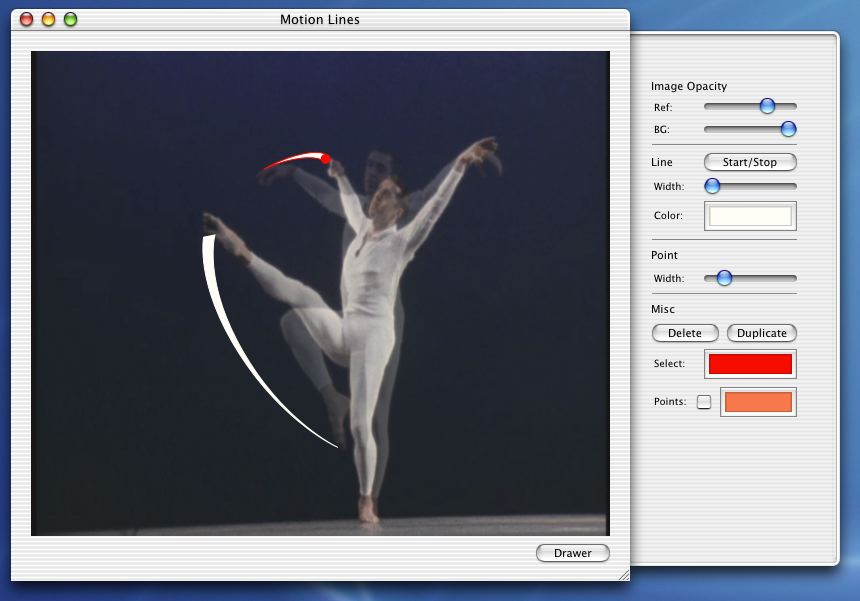

Figure 23

Figure 23: Generate motion

lines using video frames as reference

The application lets you load two images, a reference and a background

images, and adjust their opacities to view a blend of the two. The

user can then draw Bezier paths from a point on one image to the same

point on the other. Once the basic path is drawn, the user adjusts

the width at each control point along with the color/opacity of the

overall line, to create the desired effect. Once all the paths have

been drawn, the motion lines can be exported to transparent TIFF

files, which can then be composited in Photoshop into the final visualization.

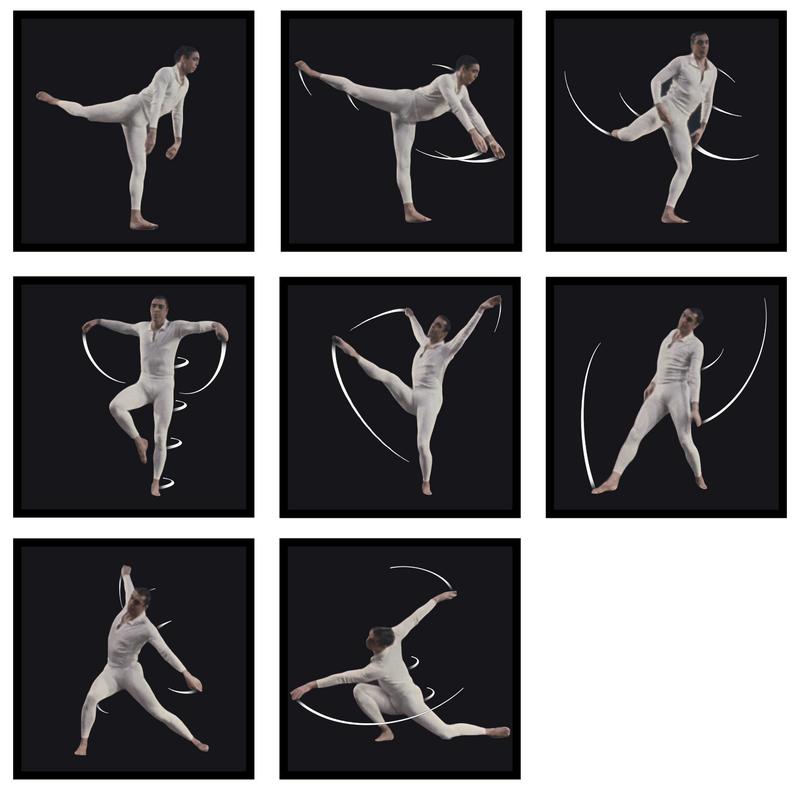

A first example of motion lines creating using this tool is shown in

Figure 24; these motion lines are on top of the

visualization shown in

Figure 17.

They help to disambiguate many of the motions, and to give a

better sense of the flow. The lines start very thin and

end wider, conveying the direction of motion without the ugly weight of

arrowheads.

Figure 24

Figure 24: Motion line comic

strip visualization.

Video

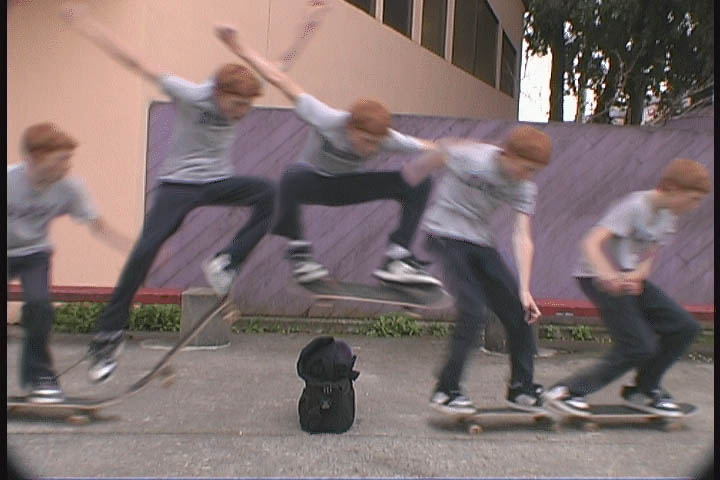

In the following visualization (

Figure 25), motions lines are used with strobing

as an alternate way to depict the

skateboard sequence.

Along with standard motion lines, red lines where the skateboard hit

the ground add another comic strip effect.

Figure 25

Figure 25: Strobing with motion

lines visualization.

Video

Interestingly, our viewer feedback suggests that motion lines affect

the above visualizations differently. In the dance sequence,

Figure 24 was widely considered to be the best

visualization among the methods presented, both in terms of

aesthetics and conveying the true motion. The skateboard

sequence, on the other hand, was deemed better visualized through

motion blur. This is probably partly due to the simplicity of

the action, the motion lines did not convey any new information.

But that is not all: one viewer remarked that he "didn't trust" the

lines in the skateboard sequence - they were "too graceful." "I expect a

dancer to be graceful, but for a skater, it just makes it seem like a

cartoon." This suggests that some sequences might be more suited

to the technique than others. More exploration into how the smoothness of motion lines

affect the efficacy of the visualization could be useful.

Motion lines and other diagramatic elements provide a huge toolbox

with which to describe human motion. In the

strobing section, we discussed the

problems that arise with image overlap, and in many cases these

disappear when using motion lines. Consider the following

visualization of sequence from a Buster Keaton

film.

Figure 26

Figure 26: Visualizing a swing

using motion lines.

Video

Note that the motion line is not restricted to being a "tail," it

spans the entire length of action. Using this diagrammatic

framework, the entire action is summarized by a single pose image,

providing a cleaner visualization than strobing or comics could

generate by themselves.

NEXT: Conclusion and Future Work